Fred Minnick truly needs no introduction, but he deserves one anyway. He is a bestselling whiskey author, a judge for the San Francisco World Spirits Competition and World Whiskies Awards, a bourbon ambassador for the Kentucky Derby Museum, a contributor to Whisky Advocate, a photographer, and a guy willing to talk bourbon with literally anyone on Twitter. Without question his face belongs on any Mount Rushmore of bourbon experts. In his fourth book (due in October), Bourbon: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an American Whiskey (BourbonRebirth, using his own hashtag), Minnick traces the entire tumultuous history of bourbon from the dawn of our nation to the present-day boom.

Last year’s Bourbon Curious: A Simple Tasting Guide for the Savvy Drinker gave a decent short history of bourbon, but the majority of the book focused primarily on how to enjoy it. BourbonRebirth is a much deeper dive: where it came from, how it evolved, what nearly killed it (several times), and how it roared back to life. Fred’s signature style reads like a magazine, with beautifully detailed side windows that include historical photos, documents, advertisements, facts, timelines and more. Occasionally the main chapter is interrupted mid-sentence by a multi-page insertion, which takes a little getting used to. However, this format really shines as a reference source, and allows for entertaining skimming while waiting for the next pour of whiskey.

Minnick remains conversational throughout, injecting his own opinions and personal experiences. He even reveals the one unicorn bottle he’s been searching for. While searching for the truth, historians must continue to draw likely conclusions without the benefit of absolute proof. Filtering his diligent research through logic, Minnick takes the reader through his investigative process. Last year, in Bourbon Curious, Minnick felt that “the sad truth is we’ll likely never know who truly invented bourbon or why he or she named it so.” Just a year later, and for the first time in print, Minnick identifies the person who likely started it all.

If this were a biography, an appropriate title might be Bourbon: A Life. From the origin of its name to the many people who came to know it along the way, BourbonRebirth leaves you feeling that you really know and understand this whiskey better. Of the many excellent books on American whiskey I’ve read, none has captured its entire history as brilliantly as this one. Minnick told me he edited down the original draft over 20,000 words. While I would love to learn much more of what he has to share, I think it was the right decision for this book. In less than 240 pages, it manages to deliver an incredible amount of information while still maintaining a reasonable pace.

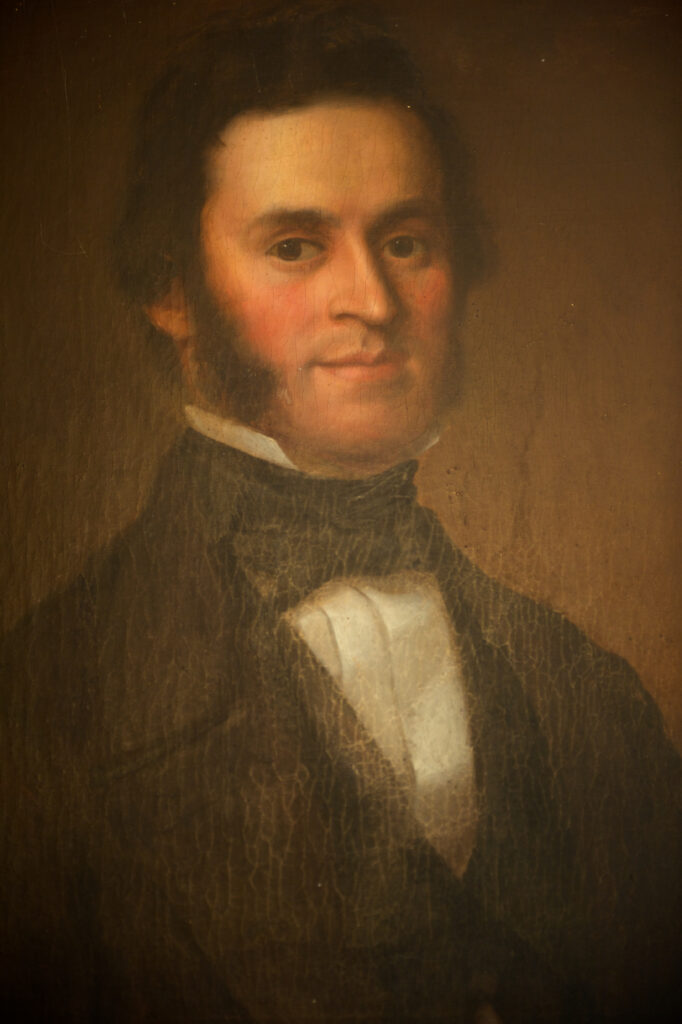

While today, people become incensed when flavoring or coloring is added to whiskey, but rectifiers used to routinely add tobacco spit and other questionable substances. Minnick credits James Crow, perhaps the first legendary craft distiller, for elevating the quality and producing the gold standard of bourbon in the mid 1800’s. Old Crow, once the Pappy Van Winkle of the 19th century, was eventually relegated to the bottom shelf. Old Crow’s salesman, E.H. Taylor, carried those values forward and was instrumental in the creation of the Bottled-In-Bond Act, which required whiskies meet certain quality standards to be bonded. The battle between distillers (who had nothing to do with bottling) and wholesalers (who did whatever they pleased to the whiskey before selling it) is a fascinating one.

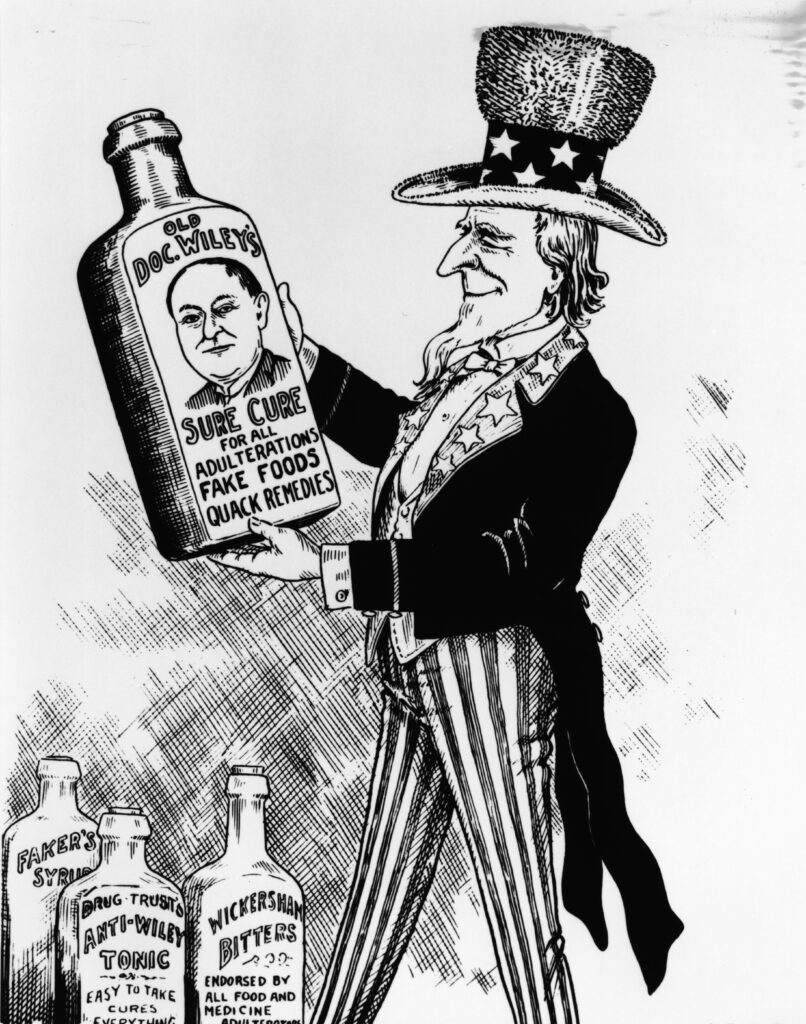

Along with the entire text of the Bottled-In-Bond Act, several other landmark pieces of legislation are presented and discussed in the book. They are also placed in a historical context. President William Taft researched whiskey and reworked The Pure Food & Drug Act of 1906 to differentiate straight whiskey from modified spirits. His Taft Decision allowed consumers to buy their spirits with confidence.

BourbonRebirth delves into the devastating effect both World Wars had on the entire whiskey industry. By twice forcing distilleries to produce only industrial and medicinal alcohol, while taxing the aged stocks of those that didn’t qualify for any production, the U.S. government nearly destroyed our country’s Spirit (pun intended).

Sandwiched in-between the wars was of course Prohibition. When the bell tolled, $400 million of whiskey sat in bonded warehouses with no direction on what to do with it. Minnick details how the medicinal whiskey exemption very much kept the distilleries alive, yet with governmental restrictions in place, even the American Medical Association was forced to purchase medicinal whiskey from bootleggers! There are already countless books about the gangsters and illegal suppliers who thrived during Prohibition (Gentlemen Bootleggers is a favorite of mine). Minnick wisely spends little time on them and instead focuses on the often-overlooked challenges facing the legal distilleries.

When FDR finally repealed the Volstead Act in 1933, it was left to the individual states to decide their liquor policies, and this helps to explain why today’s liquor laws are so varied and confusing. Bourbon has always been a valuable (and unappreciated) taxpayer and employer, and no time more importantly than during the Great Depression. It employed plenty of people and boosted multiple other industries, while being shackled by enormous taxes and constant government oversight. Capitol Hill had begun a multi-year onslaught of antitrust investigations into the distilleries, despite its own policies forcing the little guys to sell out to the bigger companies.

We often refer to the “bourbon shortage” that is occurring today, but Minnick hammers home the point that those referring to today’s environment as such could benefit from a bit of perspective. Following World War II, our closest ally Great Britain worked alongside other European nations to prevent bourbon from challenging Scotch for supremacy. Despite the U.S. placing no restrictions on imported liquors, Bourbon faced import quotas and stiff tariffs nearly everywhere. There’s some fascinating information about Japan, who loved Blanton’s from the start, despite it flopping domestically. Perhaps we deserve to not have Straight From the Barrel available in the United States.

Then the U.S. drinking trends began to change. Pappy Van Winkle himself tasted Vodka in the 1960’s and declared it “will never sell,” but James Bond’s “shaken, not stirred” hit harder with the younger generation beginning to embrace mixed drinks. In an effort to stay relevant, giants like Brown-Foreman filtered out the color of its whiskey and released a pathetic failure called “Frost.” By the early 1970’s, clear bottles lined the bars while distilleries were selling, closing or struggling to find their way.

BourbonRebirth presents the origins and story arcs of the brands we know today. We see how Stitzell-Weller was forced out of the reluctant hands of the Van Winkles, who went on to launch the Old Rip Van Winkle brand. We see the incredible effect of savvy marketing from Bill Samuels at Maker’s Mark when bourbon’s golden age had appeared to have long-since passed. Maker’s Mark may not get the respect it deserves today, but there was a time when it was the only stop on the Bourbon Trail. Its success in taking on Jack Daniel’s led to the creation of Woodford Reserve, and (like Early Times vs. Old Stagg 25 years earlier) the battle for supremacy between them ignited the entire category.

These are the best parts of the book for me, the periods of time that have been a mystery to many younger bourbon fans. Minnick brings the Rebirth into full view for the first time. We learn the story behind the huge quantities of wheated bourbon aging at Stitzell-Weller in the early 1990’s that is now among the most sought-after in the world. Companies like Jefferson’s, Michter’s and others stepped in to buy this excess whiskey and resell it. Nowadays, these non-distilling producers might be considered “inauthentic.” Back then, it was invaluable to the distilleries and they loved it.

You will read about the bars and restaurants that made whiskey cool again as well as the craft movement that has led to nearly 1,000 new distillers. Minnick has his own gift for distilling, separating the innovative, yet authentic, offerings that are now available from the flavored whiskeys and sneakily dropped age statements that come along with that. We see the rise of the Master Distillers as industry rock stars, when they used to remain behind the scenes making whiskey.

One of those rock stars, Booker Noe, introduced the first limited release small batch, which sat on the shelves. It’s hard to imagine that nobody expected the Buffalo Trace Antique Collection to be anything other than a way to try and sell old whiskey. Now these are nearly impossible to purchase at retail prices, while they are bought and sold for exorbitant prices in a secondary market. Minnick notes the irony in Buffalo Trace now calling for a shutdown of the secondary market today, when they certainly would have loved having that outlet available in the 1990’s, stuck with excess stocks of whiskey.

Both Bourbon Curious and BourbonRebirth are essential for anyone claiming to have a bourbon library. This will be the first bourbon book I recommend, and I don’t see that changing anytime soon. As acclaimed bourbon historian Michael Veach says himself, BourbonRebirth “is an instant classic.”

Recommendation: Essential.

Rating Scale:

Essential: Every home bar or library should have a copy of this

Recommended: Enjoyable read – Absolutely worth the time and money.

Average: Better presentation available elsewhere

Forgettable: I wish I had my time and money back

Note: Fred Minnick was kind enough to provide me an Unedited Proof of the book for this review